Do we really need to delete our cookies?

/There is a belief that deleting cookies from a browser leads to a drop in flight prices. But is this smart practice or simply an urban myth? Tom Woods investigates.

I wanted a flight and I wanted it for as little money as possible.

Such was the case that I employed this little trick I had recently read about on the internet – “delete your cookies and the price of the flight you have been looking at should fall,” it read.

Great, I thought. Ten seconds of my life in exchange for a reduction in the cost of this flight I am about to shell out for. Martin Lewis eat your heart out!

The result? Nothing changed. Deleting my cookies didn’t work. Though I wasn’t about to give up there.

After navigating back to the settings tab on the browser I was using, my browsing history went, the cache was cleared and passwords, autofill forms and content licences were all reset.

It HAD to happen this time. But it did not. Maybe the saying is true; you shouldn’t believe everything you read on the internet.

But still, respected publications such as The Guardian had articles backing the theory, and there are plenty of travel blogs suggesting the same.

It might not have happened to me, but that didn’t make the idea an impossible one.

Take the case of American Alejandra E from Florida, for example. She searched for flights to both Atlanta and South Africa last summer, and found out that if she browsed with cookies, the price of her flights were at around $200 more than without.

“I was searching for flights to South Africa and Atlanta at the time. They were two different trips from Orlando Airport, which is actually more expensive to fly from than [nearby] Tampa or Miami.

“For the South Africa one I looked at pretty much all available airlines and checked on the regular web browser a couple of times. Then I found out that searching on incognito mode made the prices cheaper.”

Incognito mode, also known as privacy mode, is a feature in some web browsers that allows the user to disable the web cache and browsing history allowing searches to be performed without storing local data that could be retrieved at a later date.

I was, naturally, curious and so I decided to take a deeper look.

What is a cookie?

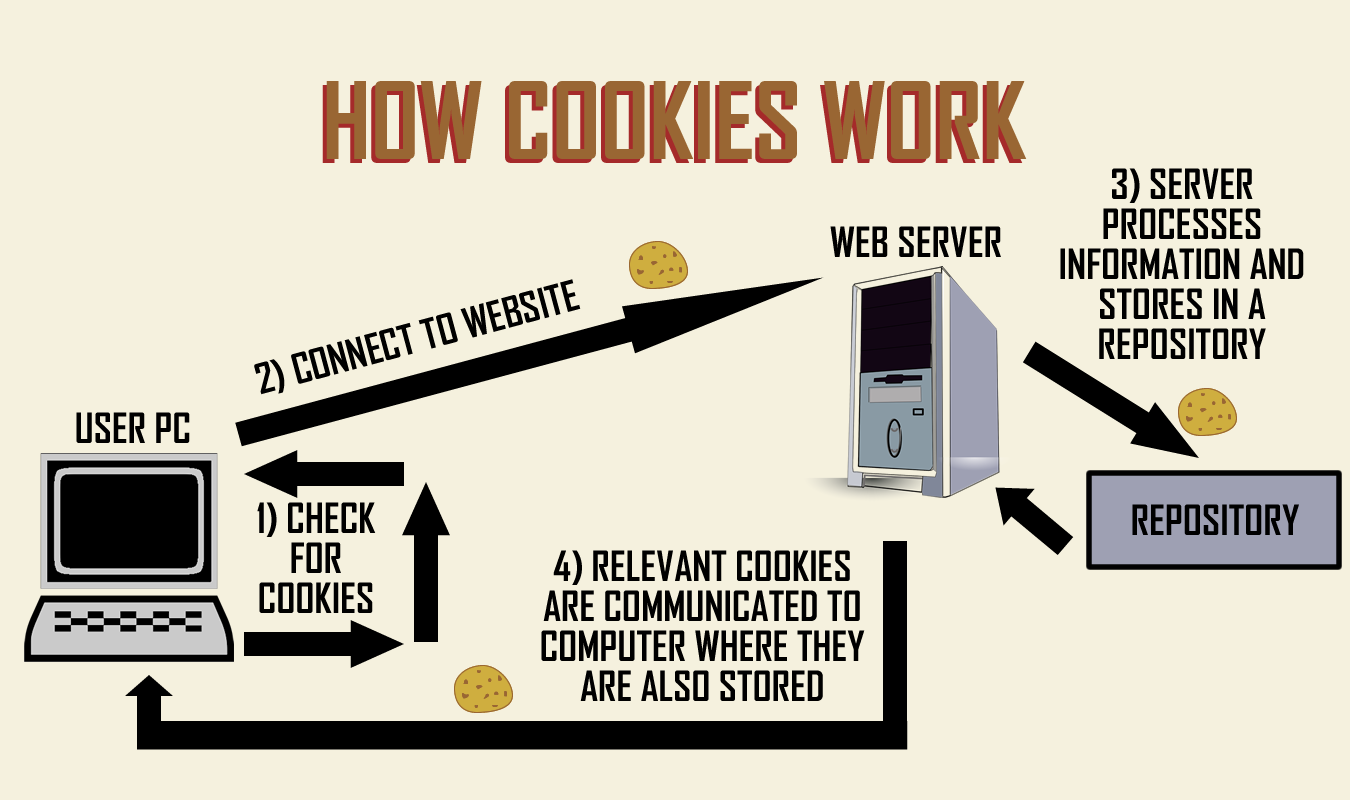

In information technology, a cookie is not a chocolate-chipped delight that you may find in the cupboard or in a biscuit jar, but rather an extremely small piece of data that a browser stores on a computer.

They help websites by holding information about you and your preferences to make for a more efficient and effective browsing session in the future.

An example of this using flight booking websites would be if the user makes a search, types in an airport of origin, destination, selects dates and then selects the number of passengers that will be flying.

Once the search has been performed, the website would send a little document, or a cookie, with that information to your computer.

The next time that website is visited, the website will read the cookie and extract that information, allowing it to pre-populate forms or adjust user settings according to the most recent data it has on record, so that a repeat search can be carried out with a single click rather than by the user manually filling out all of the information again, assuming that a repeat search is the objective.

But cookies don’t just store one certain set of information. They can contain several different aspects of a browsing session, such as language, the time and date that the website was accessed by a computer, where it was accessed from and the links clicked on any given page.

Other examples of cookie use by websites include remembering login credentials so that users don’t have to input usernames and passwords each time they visit, and the retention of items in a shopping basket by a retailer.

The belief about the negative effect, from a consumer’s perspective, of cookies on flight prices is rooted in the communication between the mode of access and the website.

If the flight operator or seller can see that you have made a certain search on their website before and that there is demand there, then it will trigger an increase in the price the flight or flights will be on sale for.

But if those cookies aren’t available for reference because they've been deleted then, in theory, how can the website possibly assess the demand and offer you anything other than the standard price? Well, it supposedly can’t.

Putting it to the test

Back in 2010 The Guardian’s Patrick Collinson experienced an upturn in price when he was searching for a return flight to Ireland for a friend. The initial search brought up a price of £187. After he double checked this price with his friend he returned to the website to book the flight – only it had risen several pounds to £212.

As Collinson put it, “an urban myth was true.”

But I wanted to test the waters myself, and set about it by doing several different searches for international flights from the United Kingdom with several different airlines, as well as looking at accommodation providers, too.

Out of the 840 tests carried out over three weeks in April 2016, which included the use of two laptops, one with and one without cookies, eight flight routes and four accommodation providers, I found discrepancy in only one such return booking.

That was with Emirates, a return route flying outwardly from Manchester to Dubai on 6 January 2017 and returning one week later on 13 January 2017.

The combined price with cookies was £797.76, but on the computer on which that data had been removed prior to searching it cost only £398.88 – a staggering decrease of exactly 50 percent.

Perhaps this was just a glitch in the system. After all, an exact doubling in the price seemed merely coincidental as only four of the 84 tests that were run using Emirates’ website produced those results.

Unsurprisingly, Emirates refuted any claim of cookies affecting prices, and offered an explanation for the sudden increase in price.

“Our booking engine works in real time availability; the fares will change depending on the availability of seats on our flights. That is why you may get different fares each time.

“Yes, the cookies won’t affect the fares,” they said.

What the travel operators had to say

Two of the operators I searched with were immediately dismissive of the theory of cookie use affecting the price of their flights, much like Emirates were.

As Ryanair publicist Aoife Van Wolvelaere explained, “this idea of ‘tracking’ or using cookies to increase air fares is a myth.

“We use an industry standard PSS (passenger service system) for managing our bookings – Navitaire – which is also used by 50 other airlines including Vueling and AirAsia.

“Ryanair offer Europe’s lowest air fares, which are sold on a first come, first served basis and rise only as quickly as the lowest fare class are sold.

“The data we collect is via My Ryanair customer registration service, which allows us to tailor our offering to individual customers.”

easyJet’s press officer Ellie Gillingham explained their strategy as well “easyJet’s pricing is demand-led, which means that as more seats are booked on a flight, the price will rise, so our fares start low and generally increase the closer it is to the date of departure.”

I also asked Booking.com to see whether accommodation websites implement cookie-related pricing strategies, but they only said the following.

“Our accommodation partners choose to work with Booking.com for the considerable benefits they receive from being part of our service in terms of increased occupancy rates and volume of reservations.

“All our rates on Booking.com are set directly with accommodation partners, which we then use to help drive businesses from a global traveller base to their brands via our channels. Our best price guarantee also ensures our customers always get the best deal – on all bookings.”

An expert opinion

But, really, this needed an unbiased viewpoint, that’s where web designer Terri, from webdesignsbyterri.com, comes in.

“It’s always been based on anecdotal evidence,” she believes. “I’ve also heard of businesses supposedly charging people using a Mac higher prices than PC users, with the theory behind that being that Mac users can afford to pay higher prices for just about everything. The case against Orbitz is a prime example.

“Based on this it’s not just cookies, which 99.9 percent of all websites use, that are suspect, it’s also which browser and which computer.

“Aside from the conspiracy theory, consider the logic of airlines doing such a thing. Putting up a different price every time you visit a site isn’t likely to make a consumer spend money.

“Airlines have other ways of increasing the cost like added charges for seat upgrades, luggage charges, travel insurance, seat selections, et cetera.

“So maybe it might work some of the time, but not most of the time. There are so many factors that go into airline fares, including which day of the week you purchase, frequent flyer membership, past purchases, travel dates and which demographic basket you’re being put into via your ISP (internet service provider) and browser, that the practice of changing rates cased on cookies would seem a very risky business for these airlines because people sue over everything nowadays.”

Conclusion

While the idea behind deleting cookies to attain lower flight prices is clearly logical when the system is broken down an assessed, the evidence already gathered would point to an outcome to the contrary.

Flight and accommodation companies are pretty adamant that there is no foul play nor any correlation when it comes to their use of customers’ browsing habits and the prices that they charge. The explanations received by the likes of easyJet and Ryanair are hardly farfetched either, yet are actually rather plausible.

While in the United Kingdom it wouldn’t be an illegal practice if it was indeed true and would bring into repute the morals and ethics of any companies performing this. Surely it is a consumer’s right to do some window shopping before making a purchase.

But still, a little part of me wants it to be true. How great would it be if there was this little-known trick to create a sure-fire saving every time someone goes to book a holiday?

Though one would have to question whether in that instance companies would mark up prices so that any ‘saving’ would not result in a financial loss of their own.

In the end, it appears as though the evidence is conclusive, this is indeed fiction, not fact. But, hey, it can’t hurt to throw away cookies in the hope that a few quid will be knocked off your next flight.

Travelling alone can be both daunting and exhilarating, so, to help with your debut, here are 11 tips for your first solo travel adventure.